Dr. Dirr's thoughts on the Eastern Arborvitae:

Not quite sure why I never fully respected this soft-textured needle evergreen but an epiphany occurred during a seven-day circuitous, whirlwind-like, 2018 tour of Vermont. From Brattleboro to Burlington, in cultivation and the wild, the species was ubiquitous. Screening evergreens are few in this cold climate state, with arborvitae and hemlock the mainstays. This comment applies to all of New England and the Midwest with arborvitaes extending into zone 8 landscapes. Abundant in the wild, the eye opener was the size, trees commonly 60’ high, varying in width from narrow to wide-spreading.

Deer damage in Miami

I noticed salt injury, cold (yes, on some cultivars), deer browsing and what appeared to be leaf miner damage. In cemeteries throughout, it was common to witness ~100-year-old trees. A reference cited a plant being over 1,100 years old. The National Champion is 113’ high and 42’ wide and located in Leelanau, MI. Arborvitae translates to the tree-of-life, thus perhaps the rationale for planting with loved ones. The other (real?) reason for the name was the use of the foliage to supply vitamin C to combat scurvy for French explorer Jacques Cartier’s men during the 1535-36 winter.

The species displays remarkable climatic and soil adaptabilities which are the foundations for its landscape ubiquity. I observed it in landscapes and/or the wild from Maine to Minnesota, south to Georgia. A native population in the Natural Bridge Park, south of Lexington, VA is the most southern native outpost I observed although it crosses over to a few counties in eastern Tennessee.

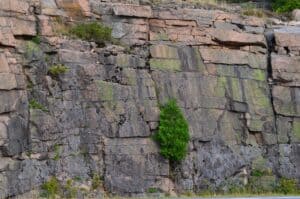

Cedar Creek produced the deep limestone gorge, some 215’ deep, providing cooler temperatures. One old trunk was about 2/3’ in diameter. Seedlings and 20-30’ high trees were present on the slopes and flood plains indicating the species is still regenerating in the area. My initial thought was focused on whether the southeast provenance would be more heat-tolerant. In Vermont and Maine, trees grow from rock fissures/crevices, in bogs and around swamps, typically in sun, but as with the Natural Bridge plants, also in partial shade.

Growth habits are remarkably diverse…tall, slender, columnar, pyramidal to broad-oval, single- or multiple-trunked and often low branched. I pin-pointed landscape size in the 30 to 40’ range but need to recalibrate after Vermont. A great attribute of T. occidentalis is its ability to withstand interminable pruning. Some hedges are at a perpetual standstill.

Foliage (needles) are 1/12” long and flattened to the stem, like shingles on the roof, soft to the touch, bright green in summer, often yellow-green to bronze in winter. Cultivars ‘Nigra’, ‘Techny’, ‘Technito’, and others are greener in winter.

Foliage (needles) are 1/12” long and flattened to the stem, like shingles on the roof, soft to the touch, bright green in summer, often yellow-green to bronze in winter. Cultivars ‘Nigra’, ‘Techny’, ‘Technito’, and others are greener in winter.

The species is monoecious, male cones small, reddish; female 8 to 10 scaled, green then rich brown at maturity, ripening in fall and persisting through winter. Seeds require a brief cold-moist stratification period. Cuttings root readily, especially after exposure to cold in fall. Bark is light gray-brown, with shallow fissures, developing fibrous threads. Wood is light, durable, rot resistant and used for furniture, especially the famous Adirondack chairs.

The species spawned numerous cultivars with dark green, blue-green, yellow, variegated, twisted, stringy foliage; dwarf, columnar, weeping habits. There is an eastern arborvitae selection for every landscape niche. In practice, the hedging/screening/cold hardy types are most in demand. In Oregon, I noticed fields of nothing but ‘Emerald’ (‘Smaragd’) most of which will be utilized in midwestern and eastern gardens but, in recent years, becoming more common in the southeast.

There is more to the Thuja story with ‘Green Giant’, a hybrid of T. plicata and T. standishii, offering deer resistance, more lustrous dark green foliage, and soft-textured pyramidal habit. To date, it has displayed high heat tolerance and become a favorite of the southeastern nursery industry. Thuja standishii, Japanese arborvitae, is a graceful species, not well known, with habit and architecture similar to Cupressus nootkatensis (formerly Chamaecyparis nootkatensis). The few specimens I observed (Missouri Botanical Garden, Virginia Tech, Hampton Roads, VA, and New Haven, CT), offer promise for selection and breeding.